Situated in the middle of the “Soul City Corridor” along Chicago Avenue and identified by the city’s Invest SouthWest initiative, PopCourts is part of a larger vision to bring development to Chicago’s underinvested and primarily Black and brown communities, a strategy that can help build social resilience. (Anezka Gocova)

Social infrastructure, or the physical spaces communities use to gather and build relationships, are critical to building resilience to fires, storms, and other climate hazards, according to arecent reportby the Urban Land Institute.

Beyond climate concerns, investing in these strategies also enhances assets and communities year-round by invigorating community life and urban livability, making it a no-regrets strategy for real estate. Areas with well-developed social infrastructure are frequently more vibrant and attractive, drawing users in, boosting foot traffic, and enhancing value for local real estate.

What is social infrastructure, anyway?

Social spaces, whether plazas, parks, entertainment centers, favorite restaurants, or more, are what transform the built environment from a collection of buildings and the areas between them into aplace, that holds connection, belonging, and meaning to the people who use it. Those connections mean social infrastructure is just as important as physical infrastructure in preparing a community to handle increasingly extreme weather.

How does social infrastructure support resilient places?

The degree to which places and spaces support successful social interactions can determine the long-term ability of a place to withstand stresses (chronic problems such as racial discrimination or rising higher temperatures) and shocks (sudden catastrophes such as a pandemic or hurricane).

Although adapting to the shocks of climate change often brings to mind investment in built or natural infrastructure such as seawalls or living shorelines, pairing that investment with spaces that foster social cohesion and community wellbeing to minimize stresses can magnify the benefits.

Take the well-known example of Chicago during the 1995 heatwave, which killed hundreds. The health impacts of the heatwave werelargely determinedby factors of wealth and race—but surprisingly, several low-wealth neighborhoods of color were among the neighborhoods with the fewest mortalities.

The key was that these neighborhoods had strong social connections and residents knew whom to check on. Literally, a knock at the door saved lives, whereas in other neighborhoods, the socially isolated were left to swelter at home alone. This is just one way social spaces build stronger communities.

社会隔离在许多p是一个日益严重的现象laces, and it undermines resilience and wellbeing.Cohousingcan be one solution for real estate to build value and community.

Building resilience through social infrastructure offers a significant opportunity that private real estate increasingly recognizes and capitalizes on. That opportunity is the chance to build stronger communities socially, ecologically, and financially, which deliver better long-term returns and meet rising expectations for places that preserve or regenerate community life, respond to accelerating climate change, and enhance urban livability.

Okay, I’m sold. Which strategies can developers use to include social infrastructure in projects?

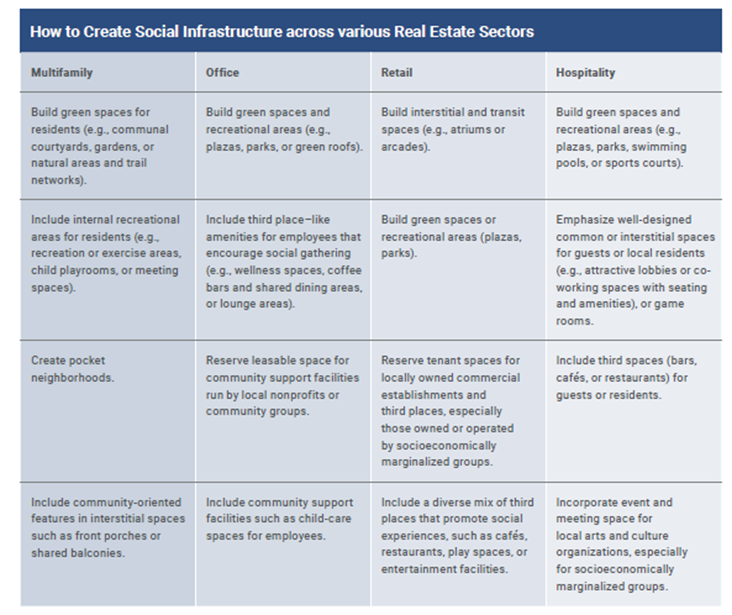

Social infrastructure can take many shapes and be built into nearly any real estate type, as the ULI Urban Resilience team’sSocial Spaces, Resilient Communitiesreport shows.

Below are three general strategies developers and owners can use when developing social infrastructure.

Below are three general strategies developers and owners can use when developing social infrastructure.

Strategy #1: Make New Space, or Activate Existing Space

The best social infrastructure happens through intentional action, design, and planning. To embed it throughout a development, space needs to be specifically dedicated to becoming a gathering point.

开发人员可以,例如,包括一个公共公园, plaza, or roof terrace; dedicate part of retail space to a locally owned café; or build a resilience hub for residents. In existing buildings, natural gathering points like lobbies or atriums can be activated to, say, host a pop-up health clinic for community members.

Different spaces serve different purposes, and their selection should be informed by carefully engaging with future users and considering how to meet community needs.

Taylor Street Apartments blends market-rate and affordable housing, common spaces for residents, public open space, and a branch of the city’s public library. (Tom Harris)

The ULI Award for Excellence-winningTaylor Street Apartmentsis a prime example – a mixed-use, mixed-income development, it blends apartments with a branch of the Chicago Public Library on the first floor. Amenity spaces such as an outdoor deck, a community room, and a fitness center were built in throughout, and the building was designed to preserve an existing community garden. Planning and careful design helps this project, which brought new affordable housing to the neighborhood, provide many valuable types of social infrastructure.

The LEED Silver building is also high performing on sustainability. Architects Skidmore, Owings & Merrill incorporated daylighting, natural ventilation, and heat pumps to reduce energy consumption, while a green roof with native plantings supports biodiversity and helps protect residents from extreme heat.

Strategy #2: Use the Spaces in Between

The surrounding fabric of buildings and spaces is sometimes overlooked as a way to support social interactions. If well-designed and maintained, the areas around and between the main programs of a development are where people cross paths, bump into each other, have impromptu conversations, and deepen relationships.

With this strategy, developers and owners can focus on the places where people might gather, and create or improve existing pedestrian walkways and paths, high-quality streetscapes, and pleasant, shared building entrances, atriums, or seating areas.

The Mariposa District was designed for greater social cohesion through spaces such as enhanced streetscapes, public plazas, and green spaces, resulting in documented increases in resident health. (John Pettigrew)

TheMariposa District in Denver, Colorado前女友emplifies this approach. A well-known development that has received multiple awards for its people-centric design, this project redeveloped an aging public housing community. Design and engineering firms Mithun and Wenk Associates focused on enhancing streetscapes with wider sidewalks, better lighting, extensive tree planting and seating, and green infrastructure to manage flooding and heat impacts; built in public plazas for community events and festivals, which are activated with large public art; and incorporated small courtyards around building units.

Post-occupancy surveys of residents overwhelmingly identify a strong sense of belonging and social cohesion and an impressive 30 percent reduction in crime rates from 2005 to 2011.

Strategy #3: Mix Uses

This strategy may feel like “been there, done that,” but in many communities, large swaths are still zoned for single uses. However, developments that serve multiple functions can attract more types of users and meet a variety of needs, helping ensure spaces are activated throughout the day and creating more opportunities for social interaction.

Creative combinations also support dynamic, diversified places that help keep an asset relevant as space demands change over time. This can happen across any asset type—for example, an office developer that also builds in entertainment spaces can ensure the property does not empty out after typical work hours but instead hosts people enjoying leisure time together.

Oasis Terraces combines a polyclinic with a community plaza, communal gardens, play spaces, gyms, retail, and dining. Outdoor areas are richly planted with terrace greenery intended to be maintained by neighborhood residents. (Hufton + Crow)

Oasis Terracesin Singapore shows the possibilities of this strategy. Designed by Serie Architects for the Singapore Housing and Development Board, the building is intended to be the mixed-use social heart of the neighborhood. The building will be home to new healthcare facilities, a community plaza, communal gardens, play spaces, gyms, retail, dining, and learning spaces.

This intensely varied mix provides something for everyone, ensuring that the building remains in vibrant use at nearly all times. What’s more, outdoor and indoor spaces are naturally ventilated and shaded by vegetation, keeping it comfortable in Singapore’s hot and humid climate. Despite its waterfront siting, it remains resilient to flooding as the ground floor is elevated above base flood elevations, while a detention tank belowground collects runoff to reduce flood risk to surrounding areas.

Conclusion

Social infrastructure is by no means a new idea—it has long been a part of urban places of all scales. However, commercial real estate is in a prime position to use this tool to support resilient, attractive, equitable places. As the effects of climate change compound on the ever-changing mix of forces shaping how cities are used (pandemics, economic ups and downs, migration), the case for utilizing the power of social infrastructure to improve community wellbeing and preparation for a riskier future grows clearer every day.

Learn more through the ULIUrban Resilience team’s workand theSocial Spaces, Resilient Communities: Social Infrastructure as a Climate Strategy for Real Estatereport.